May 24, 2022

Jeremy Denk's Music and Memoir

Timothy Pfaff READ TIME: 5 MIN.

There may never be a sunset clause on Vladimir Horowitz's famous quip, "There are three kinds of pianists: Jewish pianists, gay pianists, and bad pianists." His reputation as at least one of the GOATs (Greatest Of All Time) gave him the latitude to make the pronouncement. Yet, it warrants a moment's notice that he was staking claim to his turf in two of the categories, the second surreptitiously.

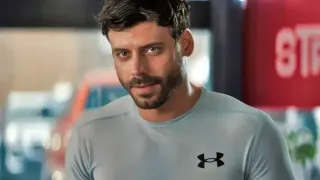

In his brilliant, hearts-and-minds-winning new memoir, "Every Good Boy Does Fine" (Random House), pianist Jeremy Denk comes out. It's not the point of his memoir, but neither is it a footnote. To borrow a music term, it's a pedal point, that is, a deep note that's sounded often enough to establish a key. (I'm not being technical here.)

Clearly Denk has included his coming-out story in what the book's subtitle calls "A Love Story, in Music Lessons" because he needed to. But he did not need to in order to address, up or down, a wink-wink about his sexuality. It's not that no one else cared about Denk the man, but that no one was winking, what with all the other things there were to marvel about in the guy, one of those truly rare humans in whose presence everything seems better and brighter.

There's nothing all that unusual about a brainiac concert pianist – or even one who, like Britain's Stephen Hough, has had that genius baptized with a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship, as Denk's was in 2013.

A startling number of pianists are equally adroit on the computer keyboard, and a few – Charles Rosen and Alfred Brendel spring to mind – have ended their careers more renowned as cultural commentators along the lines of Thomas Mann and Theodor Adorno, neither of whom was primarily a pianist, than for their prestidigitation skills at the old 88. (These will be fighting words for some; welcome to Piano World.)

What makes Denk's verbal brilliance so distinctive is not just its acuity but its indefatigable good nature (a quality he shares with Hough, arguably the outest of today's major pianists). A famously collegial musician, coming from a space as personable as it is personal, Denk has written a damn good book.

Good Thing

The title had to be his. The initial letters of the phrase "every good boy does fine" name the notes on the ascending lines on the treble clef (note how quickly this sentence has become technical), as foundational a mnemonic as there is anywhere in music instruction.

As a gay man scarred by piano lessons as a boy, and once the editor of a national magazine devoted to piano-playing, I can affirm that every good boy does not do fine, at least when it comes to tickling the ivories. And that practice alone doesn't make perfect.

The harrowing truth is that the world is crawling with really, really good piano players. It's a brutal world in which to forge a career, and success is not proportional to talent or diligence. As every musician knows in the pit of their stomach, you have "the thing" or you don't – and even the thing is no guarantor of a career.

Denk's is an American story, more than that of America's most famous pianist, Van Cliburn, the silver spoon in whose Texan mouth produced the only ticker-tape parade for a musician in American history. Denk was not, as a concert pianist, inevitable.

The most heart-warming chapters in "Every Good Boy" are about the teachers, the likely and the unlikely, the good, the bad, and the formative. If the very compound noun "piano lessons" produces a salty taste in your mouth, you will take to these passages like rescue narratives.

Organized around the principles of harmony, melody, and rhythm, the chapters in Denk's book, each of which is headed by a program of relevant piano pieces, move seamlessly between technical matters and those of the heart. He's become the teacher he would have wanted and, looking back, had, by good and bad example.

Encounters

Denk was not a prodigy in the arena of gay sex. He writes credibly about going into Central Park to study a Monteverdi madrigal ("Zefiro torna," of course) and not understanding he was in a cruising zone until a stranger gestured at him leadingly, then left in a huff when Denk sank his face back into the score. Then there's a bumbling encounter with a man named Danny. ("We fumbled with each other before falling asleep.")

He then recounts stepping onto the stage of genuine sexual and romantic contacts with other men as the equivalent, for those of us in the audience, of stepping onto stage – into the mouth of the wolf, as performers say. When he speaks of finally looking another man full in the eye, don't be surprised if yours tears up. "My body had been waiting for me all that time," he writes, "waiting for my mind to find it."

Like its author, this book is about many things, music and piano-playing only the most obvious of them. I could name the out performing pianists I know of with the rest of my word count, but I won't. It can only mean the world to the others that a musician in every sense as bright as Jeremy Denk has testified. "Every Good Boy Does Fine" could even save lives.

The book ends with a zesty tour of Mozart's C-major Concerto, K. 503 – the kind of music writing that makes you pant for the sounds. You need go no farther than Denk's new CD, with longtime colleagues of the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra, in which he is both soloist and conductor.

'Jeremy Denk, Every Good Boy Does Fine: A Love Story, in Music Lessons,' Penguin/Random House, 370 pages, $28.99 www.penguinrandomhouse.com

Jeremy Denk, Mozart Piano Concertos K. 503 and K. 466, Rondo K. 511, St. Paul Chamber Orchestra, Nonesuch. www.nonesuch.com

Help keep the Bay Area Reporter going in these tough times. To support local, independent, LGBTQ journalism, consider becoming a BAR member.