Nov 9

Kiss-In Revolution: How Public Displays of Queer Affection Became Radical Acts of Love

READ TIME: 3 MIN.

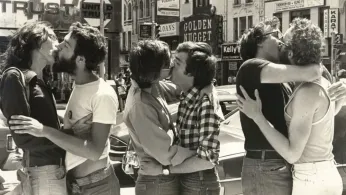

Imagine this: hundreds of queer folks streaming through Greenwich Village, hands clasped, lips locked, the air charged with possibility. On June 28, 1970, just a year after Stonewall, the newly emboldened LGBTQ+ community marked its first anniversary with a march that ended not in quiet protest, but in riotous affection. Shirtless activists kissed and held hands openly, their bodies and love on unapologetic display—a scene that would reverberate through decades of queer activism .

This wasn’t just romance—it was rebellion. In a world where queer affection was criminalized, these “kiss-ins” transformed public displays of love into radical statements: “We’re here. We’re queer. Get used to it.”

The earliest kiss-ins were acts of direct resistance against exclusion, shame, and violence. In 1970, activists staged a “kiss-in” at a New York bar that had ejected two men for kissing—turning rejection into a rallying cry . A year later, lesbian activists in Los Angeles took over a restaurant that threatened to expel two women for holding hands, demonstrating that tenderness between women could be both public and political.

This tactic soon crossed the Atlantic: the UK’s first Gay Pride Parade in 1972 ended with a mass kiss-in in Trafalgar Square, drawing thousands . As the 1970s wore on, queer kisses became street-level resistance, with Toronto activists staging a kiss-in at Yonge and Bloor after two men were arrested for kissing at the intersection—a moment that transformed a city’s crossroads into a stage for liberation .

By the 1980s and 1990s, kiss-ins took on new urgency. Amid the HIV/AIDS epidemic and the accompanying surge in homophobia, activists wielded public displays of affection as a weapon against stigma. ACT UP, the legendary grassroots group, staged its first major kiss-in during the 1988 ACT NOW National Spring AIDS Actions—over 1,000 protesters kissing in Sheridan Square at the end of the Christopher Street march .

Queer Nation, founded in 1990 by AIDS activists from ACT UP, made kiss-ins a centerpiece of their campaign against homophobia and heterosexism. Their rallies, like the 1992 Valentine’s Day kiss-in at Cornell University, embraced a “public, provocative, and highly visible approach to activism,” as described by Ithaca chapter member Paisley Currah: “a national movement to combat heterosexism and homophobia” .

In 1991, Queer Nation crashed the 64th Academy Awards with a kiss-in, blocking entry and making headlines: “We mashed our faces together and dared Hollywood to look away,” one participant recalled .

Kiss-ins are far more than a protest tactic—they’re a celebration of queer love, bodies, and joy. “A kiss is not just a kiss when it’s forbidden,” wrote historian Marc Stein, “It’s a declaration: We exist. We love. And we will not hide.”

For many, the kiss-in is a cathartic, communal experience—a moment where LGBTQ+ people reclaim the public space so often denied to them. Flyers for Queer Nation’s kiss-ins depicted multiracial couples kissing, challenging not only homophobia but racism and exclusion within the queer community itself .

Kiss-ins also upend the very meaning of PDA: what might be mundane or even frowned upon for straight couples, becomes a flashpoint for queer politics. Each kiss-in is a performance—of pleasure, intimacy, solidarity, and resistance. As one activist put it, “We’re making out for a cause. And you’re gonna have to watch.”

As Pride festivals and marches continue to sweep the globe, the kiss-in endures as a symbol of defiance and unity. In an era where backlash against LGBTQ+ rights persists, kiss-ins remind us that queer visibility is still a radical act. Whether in the heart of London, the streets of New York, or on university campuses, the simple act of kissing signals resistance to erasure—and a celebration of chosen family.

So next time you see two people kissing at Pride, remember: it’s not only passion—it’s protest. It’s a legacy of generations who risked arrest, violence, and exclusion for the right to love openly. It’s a reminder that every queer kiss, public and proud, is part of a movement that refuses to be silenced.

Because for us, love will always be revolutionary.