Apr 24

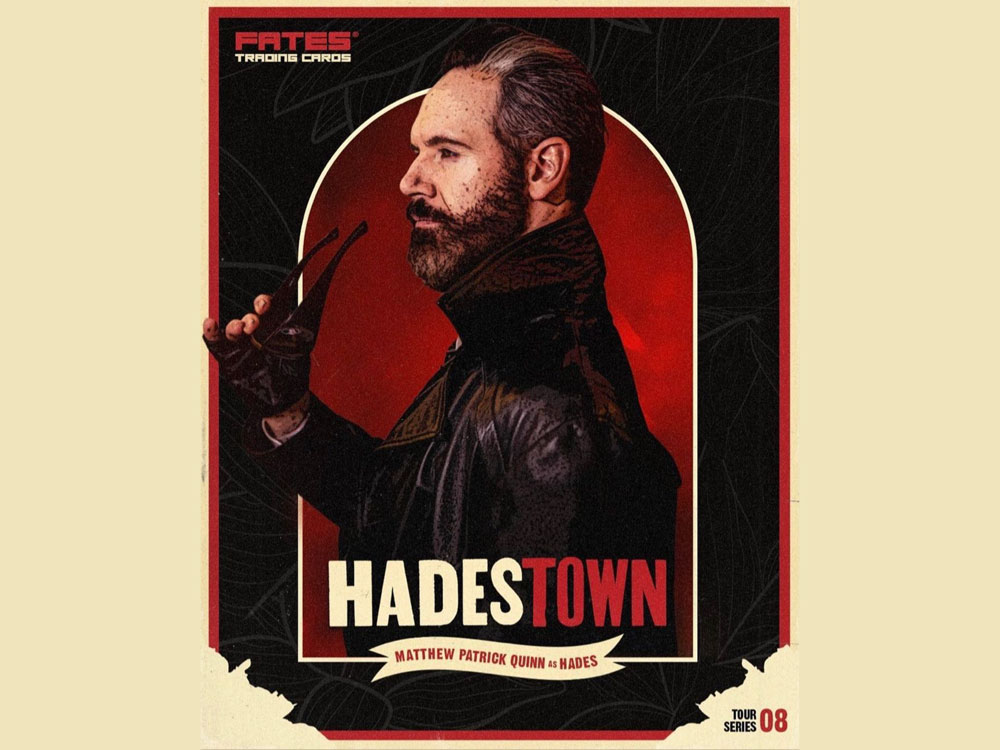

Meet Matthew Patrick Quinn – The Underworld's Seductive Daddy in Touring 'Hadestown'

Kilian Melloy READ TIME: 10 MIN.

Source: Instagram

Who can blame Eurydice for being seduced by the lean, hunky Quinn? His Hades is an aloof, charismatic figure, confident in his power and defiant at showing any vulnerability. He commands the stage with his strikingly handsome looks and an assured baritone that lets everyone know just who is in charge. He doesn't, though, make his presence known until the end of the first act, when he expresses his divisive political views in the show-stopping "How We Build the Wall," a song that expresses how his power rests in demonizing others – a method that has becoming a far more dangerous and common practice in 2024.

Quinn sees how this resonates for the queer community given the malicious – and absurdly unjustified – attempts to deny and roll back our civil rights. Quinn notes that society is conditioned to be terrified of "the other," as well as of poverty and other hardships. The 1%, he notes, have outsized influence over the lives of everyone else, not least because of the enormous political and economic sway they wield.

Quinn doesn't see Hades as a villain – at least, not in his own eyes. Hades considers his workers his "children," and sees himself as providing them the means to survive. The fatal and seemingly arbitrary condition he imposes on the lovers is a matter less of cruelty than of a painful economic reality: Orpheus' arrival has reminded the workers that a better life is possible, and his plea for Eurydice's return gives them hope. Nor is it Orpheus' music that seals the deal; rather, Persephone, moved by the young couple's love, intercedes on their behalf.

"Persephone comes to Hades and says, 'Let them go'," Quinn notes. "'What are you so afraid up? Just let them go.' But in Hades mind it's like, 'You give them an inch, what's gonna happen after that? I let her go, then you're gonna see all the rest of them [want to go.] They're gonna start a riot. There's gonna be an uprising'."

Source: Instagram

Quinn also points out that Persephone's long connubial visits with Hades are, initially, the reason for the world's climate crisis.

"In the original text, it's actually Zeus that comes to Hades and says, 'Look, something's gotta give. We can't do it this way'," Quinn adds. "And so that's why Hades agreed to let her go for six months out of the year, and it's during that time period that he starts to mine the riches of the earth to impress her."

Hades is like some "Gilded Age" robber baron in overdrive, who is pushed by "insecurity and jealousy" about Persephone's long absence to wreak havoc on the Earth. "The oceans rise and overflow, and people are starving," Quinn says. "The metaphor there is that the more he destroys the planet from within, it more it affects the cycle of the seasons on Earth. You can see right there that metaphor for big business destroying the planet."

Clearly, this is not your typical retelling of the story of Orpheus and Eurydice. Fittingly, the show does not sound like a typical Broadway musical. Its long route to Broadway began in 2006, when Mitchell, a singer-songwriter who wrote the music, lyrics, and book, staged her DIY version in her Vermont hometown. Mitchell continued to develop the musical, turning it into a best-selling concept album in 2010. After meeting Rachel Chavkin in 2012, the two began collaborating on the musical's next iteration, which took it off-Broadway, to Edmonton, Canada and London, England, before it arrived on Broadway in 2019, winning the Tony for Best Musical, as well as Best Score (Mitchell) and direction (Chavkin).

"I absolutely love it," Quinn says of the music. "I mean, it sort of defies description because it's such an amalgamation. Mitchell comes from a folk background, and she's mixing folk music with New Orleans-style jazz, and then wrapping it in musical theater style.

"At the heart and at the core, it's folk and jazz," Quinn adds, "but then you add in a little bit of that classic musical theater sound." The result, he adds, "is something that's so vastly different, and each song has its own style."

Source: T. Charles Erickson

That probably can't help but appeal to Quinn, given that he didn't have formal voice training when he first started doing musical theater. "I thought, 'I can do that. Let me give that a try'," Quinn describes his entrée into the genre. "I basically just imitated Broadway recordings that I listened to. Later on, I would sort of pepper in a couple of classes here and there to prepare for an audition or whatnot.

"I had to learn some skills specifically for this show," Quinn adds, "because the voice arrangement for Hades is fairly low. It was a matter of fine-tuning that skill to create that sound."

Speaking of long separations from family, the national tour of "Hadestown" has meant more than a year on the road for Quinn. It's part and parcel of the artist's chosen career. "Every tour that I've done has a different significance in my life," Quinn tells EDGE. "The piece itself will influence my emotional state, or will reflect on where I am currently in my life as a performer, as a citizen, as a gay man.

"This one is absolutely fulfilling on every level – as an as an artist, especially – because it's just such a beautiful piece of work," Quinn goes on to say. "I think it's one that really needs to be seen and can have great effect and change on society."

Watch this conversation between Matthew Patrick Quinn (the National Company's Hades) and Zachary James (the UK Hades) on Instagram.

Maybe so. After all, the story of Orpheus and Eurydice has proven its staying power, persisting for millennia and continuing to inspire art. French filmmaker Jean Cocteau gave the story what was, at the time, a contemporary treatment in the surreal 1950 film "Orpheus"; Claudio Monteverdi broke fresh ground musically and dramatically with his 1607 opera "L'Orfeo"; and just recently, composer Matthew Aucoin returned to his native Boston with a re-orchestrated version of his 2020 opera "Eurydice," boasting a libretto by playwright Sarah Ruhl, based on her 2003 stage play of the same title.

"It has everything," Quinn notes of the enduring myth. "It has a dramatic love story that's a tale as old as time. How many stories do we know where you meet a pair of lovers who have to go through some sort of traumatic experience? The story has all the things that keep us interested, but I think what is the most fascinating about the Orpheus story is that – I don't want to give anything away, but most of us know how it how it ends."

Let's just say it's a heartbreaker.

"I think that's what fascinates a lot of people wanting to try to give their spin on, 'What does that moment in the show mean? Why is that moment so important?'" Quinn ruminates. "I think that's why so many artists, so many directors, so many writers want to take a stab at the Orpheus story – because they want to tell their version of what it means."

Timeless as the tale may be, as noted earlier, "Hadestown" is very much of the current moment: Climate change, workers' rights, the darker side of capitalism, the right of people in love to be together... is there a hot-button topic confronting us right now that the stage musical doesn't take on in the course of its three-dozen-plus highly catchy, energetic songs?

Laughing, Quinn tells EDGE: "It really does hit many, many points. If you come and see it and you tell me one that's missing, I'll call Anaïs and tell her she has to do some edits."

"Hadestown" plays at the Boch Center in Boston's theater district April 23 – 28. For tickets and more information, follow this link.

Kilian Melloy serves as EDGE Media Network's Associate Arts Editor and Staff Contributor. His professional memberships include the National Lesbian & Gay Journalists Association, the Boston Online Film Critics Association, The Gay and Lesbian Entertainment Critics Association, and the Boston Theater Critics Association's Elliot Norton Awards Committee.